On a chilly March morning in 2002, Miguel Santos Rodriguez stood in the gritty expanse of Patterson Auto Salvage in Detroit, pulling the hydraulic lever of the car compactor. The machine groaned as it crushed another vehicle into a twisted metal block. It was routine work for the 28-year-old yard worker, but something about the 1993 Ford Crown Victoria caught his eye. Faded blue stripes peeked through its white paint, hinting at its past as a police car. As the compactor pressed down, a dark object fell from the collapsing roof, landing near Miguel’s boots. He stopped the machine, climbed down, and picked it up—a Kevlar police vest, standard issue, with a name tag: “DTR Morrison, Detroit PD, Badge 847.” A chill ran through him. Something was very wrong.

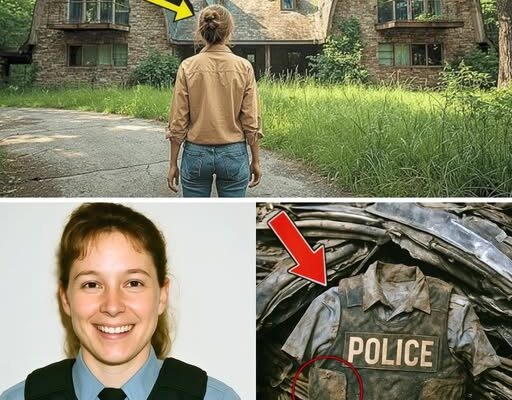

Miguel checked his watch: 9:47 a.m. His supervisor was still at the office, an hour away. The vest bore a date stamp—issued December 1994—and legible serial numbers on the Velcro straps. Using his disposable camera, Miguel photographed the vest, the car, and its VIN plate: 2FALP71W5PX123847. Inside the glove compartment, he found paperwork showing the car was sold at a Detroit Police auction on November 18, 2001, to Hutchkins Auto Parts in Corktown. Sensing the gravity, he called the office. “Janet, it’s Miguel. I found a detective’s vest in a police car. Should I stop everything?” Janet’s voice tightened. “Detective R. Morrison? Hold everything. I’m calling the police.”

Within 37 minutes, Detective Sarah Kowalsski arrived with Officer James McNeel. Kowalsski, in her early 40s, with graying hair in a tight ponytail and a no-nonsense brown leather jacket, carried a metal clipboard. “You found this?” she asked Miguel, flashing her badge. He recounted the discovery, pointing to the vest now secured in the supervisor’s office. Kowalsski examined it, her face darkening as she read the name tag. “Detective Rebecca Morrison,” she said softly. “I knew her.” McNeel added, “She disappeared in 1994. Case went cold after six months. This is the first real lead since.”

Rebecca Morrison, a 29-year-old Detroit PD detective, vanished on September 23, 1994, after leaving her precinct at 11:30 p.m. Her blue 1991 Honda Accord was found two days later in Hart Plaza’s parking lot, with no signs of struggle or foreign fingerprints. Investigating corruption in the department, Rebecca was building a case against evidence tampering and bribery involving high-ranking officers. The official theory—that she fled to avoid testifying—never sat right with her family or colleagues, who knew her fierce dedication. Her brother, Thomas Morrison, had spent eight years organizing searches, hiring private investigators, and offering rewards, never giving up hope.

Kowalsski’s investigation kicked into high gear. The forensics team, led by Dr. Susan Fletcher, found hair fibers, fingerprints, and dried blood in the Crown Victoria’s trunk. The blood matched Rebecca’s DNA from her personnel file. The car’s maintenance records showed it was serviced three times between 1994 and 2001 by Hutchkins Auto Parts, owned by Chief Daniel Hutchkins—promoted to chief of detectives in 1995, a year after Rebecca’s disappearance. Kowalsski drove to Hutchkins’s Corktown warehouse, a sprawling lot filled with dismantled police cruisers. Hutchkins, 53, tall and silver-haired, greeted her in crisp mechanic’s coveralls. “Detective Kowalsski, what brings you here?” he asked, his tone smooth but guarded.

She confronted him about the vest and the car’s history. Hutchkins shrugged, claiming he bought dozens of auction vehicles and couldn’t account for leftover items. But Kowalsski spotted a blue 1991 Honda Accord in the yard, its VIN matching Rebecca’s personal car. Purchased in April 1995 from Metro Insurance Salvage, it was declared a total loss after being “abandoned.” The paperwork raised red flags—Thomas swore the family never filed insurance claims or declared Rebecca dead. Someone had forged the documents. Hutchkins’s wife, Janet, nervously confirmed handling the transaction, claiming the insurance company offered a discount. The pieces were aligning too neatly.

Thomas Morrison, now 34, lived above a hardware store he managed, his apartment a shrine to Rebecca’s memory—photos, commendations, and stacks of private investigator reports. When Kowalsski shared the findings, he revealed a bombshell: Rebecca had mentioned Chief Hutchkins as a key figure in her corruption probe, alleging he sold seized drugs through informants. Thomas handed over his own files, detailing timeline discrepancies and ignored witnesses, including Dorothy Williams, who saw a woman matching Rebecca’s description forced into a sedan near Hart Plaza on September 24, 1994, and Carl Jensen, a marina guard who witnessed two men loading a human-sized object into a boat registered to Hutchkins’s Great Lakes Marine Services at 3:15 a.m. on September 25.

Kowalsski tracked down Dorothy, now 72, who recalled a tall, authoritative man resembling Hutchkins. Jensen, retired in Florida, confirmed the boat’s registration: MI7394BP. Both witnesses had reported their sightings in 1994, only to be dismissed. The pattern was clear—someone, likely Hutchkins, had buried evidence. Kowalsski interviewed detectives Robert Anderson and Maria Gonzalez, who admitted Hutchkins instructed them to “adjust” evidence logs to hide missing cocaine—hundreds of pounds unaccounted for, generating $50,000 monthly for Hutchkins’s network.

The breakthrough came when Thomas searched Belle Isle, guided by Rebecca’s clue: “where we used to watch the ships come in.” Near an abandoned Coast Guard station, he found three manila folders hidden in a foundation gap, wrapped in plastic. Rebecca’s files detailed 800 pounds of missing cocaine, financial transactions linking Hutchkins to informants, and surveillance photos of him with dealers. A note dated September 20, 1994, read: “Hutchkins knows I’m investigating him. If something happens, these files will prove everything.” A sealed letter to Thomas urged him to take the evidence to the FBI, warning against trusting Detroit PD.

Kowalsski and Detective Michael Donnelly, now leading the case after Hutchkins reassigned Kowalsski, met Thomas at Belle Isle. The files were a goldmine—photos of Hutchkins loading drugs onto his boat, bank records, and an organizational chart naming seven officers, 12 informants, and five civilians in a $75,000-a-month drug ring. FBI Agent Jennifer Williams joined the case, recognizing federal implications. As search warrants hit Hutchkins’s properties, he fled, withdrawing $47,000 and buying camping gear. A manhunt ensued, ending in Ohio when police trapped him at a truck stop on Interstate 75.

During his arrest, Hutchkins dropped a bombshell: “Detective Morrison is still alive.” He claimed she was held at his brother-in-law Robert Hutchkins’s farmhouse in Lenawee County, moved there in 1995 after six months in his marine warehouse basement. Photos in his briefcase showed Rebecca alive but captive, the most recent dated a month prior. In interrogation, Hutchkins admitted keeping her alive to extract information about her evidence caches, which implicated DEA agents, state police, and politicians. He demanded immunity, but the FBI prioritized Rebecca’s rescue.

At 4:45 p.m., FBI tactical teams stormed the farmhouse. Robert Hutchkins, believing he was guarding a corrupt officer, surrendered without a fight. Rebecca, found in a reinforced basement room, was weak but alive after eight years of captivity. Malnourished and traumatized, she was rushed to intensive care. Dr. Patricia Rodriguez noted muscle atrophy but no life-threatening conditions. In a brief interview, Rebecca said, “I knew someone would find my files. I just didn’t think it would take eight years.” She detailed her 1994 kidnapping by Hutchkins and two accomplices, her repeated escape attempts, and her mental strategy of documenting everything to survive.

Rebecca’s testimony led to 30 arrests, including Hutchkins, sentenced to life without parole for kidnapping, drug trafficking, and corruption. Robert received 25 years. Twelve officers, three DEA agents, and others faced 5-15 years. Rebecca’s files exposed a network generating $12 million, compromising hundreds of cases. She returned to duty in 2003, heading a new internal affairs division, overturning 67 wrongful convictions. Thomas founded the Morrison Foundation to support missing persons’ families, while Kowalsski, promoted to lieutenant, led the cold case unit.

At a 2003 City Hall event, Rebecca addressed a packed room: “Eight years ago, I sought to expose corruption. I never imagined it would cost me eight years of my life. But the resilience of my brother, Lieutenant Kowalsski, and this community brought justice.” Her book, Captive Truth: A Detective’s Fight for Justice, became a bestseller, funding victim support. The scandal spurred reforms—new evidence protocols, independent corruption reporting, and community policing. Rebecca’s survival and courage transformed Detroit PD, proving justice, though delayed, could triumph over corruption.